"Lights! Camera! Action!" So began the musical number that would be known as the Tour de Force number in 'A Star is Born' (1954).

The first time 'A Star is Born' was brought to the screen was in 1937, when William A. Wellman directed Janet Gaynor and Frederic March as the stars of the picture. The 1954 remake was devised as a comeback for Judy Garland, who parted ways with MGM and filmmaking in 1950, but was riding a high after her successful concerts at the London Palladium and The Palace in New York in 1951 and 1952 respectively.

Moss Hart, author of some of the most famous plays in American theatre, was signed to write the screenplay for the remake that was to become a musical to show off Garland's talents. As no original scripts were available, Hart started off by rewatching the 1937 version various times to outline the structure, characters and situations.

For the Tour de Force number, Hart stayed true to the 1937 film, but added a musical number. As Norman (James Mason) has been let go by the studio, Esther's (Judy Garland) star is rising. In an attempt to cheer Norman up, Esther puts on a show in their living room. As written by Hart:

For this scene composer Harold Arlen and lyricist Ira Gershwin wrote a song called 'Someone at Last'. It was written as a parody on musical production numbers, but incorporating all of Hart's instructions proved to be a challenge for choreographer Richard Barstow. So Garland and Sid Luft (producer of the film and Garland's husband at the time) turned to composer-arranger Roger Edens for help. Edens had worked with Garland from the beginning of her career at MGM and played an important role in shaping her voice and teaching her how to deliver a song, sometimes underplaying her voice instead of using it at full power all of the time, as she was used to doing in Vaudeville.

In early January 1954, Garland and Edens started rehearsing the number, making an audio recording of their ideas for the number. In 10 minutes and 25 seconds they play out the number, with Edens taking on the role of Esther Blodgett and Garland singing parts of the song or providing sound effects and commentary in the background. The number starts by Esther telling Norman about the big production number they started shooting, "it starts in an Orphans home, and I'm an Orphan," says Edens. The idea was that Esther would be playing an orphan who dreams of searching for the someone for her, looking for him through mist, fog and smoke, in Paris and Japan, the jungle and Brazil, eventually become a nurse for the Red Cross in the Battle of the Bulge. "You die," says Edens in a deadpan way. But then comes the big finale: the real her, still dreaming at the washtub in the orphanage, "has finally realized she's been missing an absolute bore and starts singing the finale, but they worked it out for a big, terrific shot —the finish shot, where the camera zooms in to this tremendous close-up of me, just as she starts into the finale", finally finding that someone for her.

Using this recording as a guideline, the number was reworked by Hart and orchestrated by Ray Heindorf. This fed Barstow's imagination and he started working on the choreography for the number, using the furnishings of the living room as props. The idea of the orphanage was dropped for the final number, but many of the elements that Garland and Edens had improvised stayed in the film, with the "big, fat close up" eventually becoming the figurehead of the film.

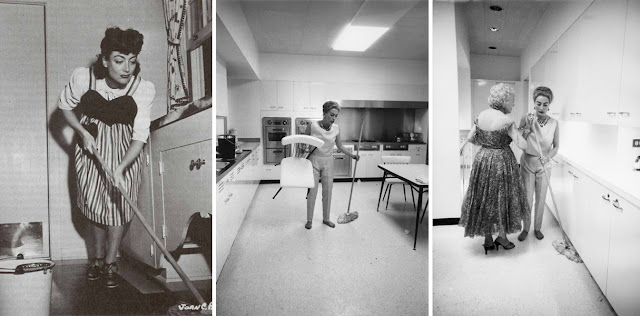

Recording of the scene began on February 4 and took four days and two cameras to finish. In the seven minutes that the number would eventually become to last, Garland dances through the living room using virtually everything she can find as a prop to illustrate the grandeur of the production number, a true tour the force to entertain Norman. A standing lamp becomes the light, a tea cart becomes the camera and jumping up on a coffee table, she's ready for action.

There's still the smoke (produced by fervently puffing on Norman's cigarette), the music of harps (a stool with its pillow removed) and voices of angels. Then in Paris Esther becomes a traffic leader, a burlesque dancer covering (and then exposing) her breasts with two leaves taken from the vertical garden on their living room wall and a can-can dancer using a ruffled pillow as skirt. In the recording Garland and Edens also improvised Edith Piaf singing "the eternal tragedy of woman", but Piaf didn't make it to the final version.

All of a sudden they are in Asia, mimicking traditional dances and donning a lampshade as a surrogate for a traditional hat. They don't stay in Asia for long, though — within a few seconds they are in Africa, with Esther grabbing the leopard skin rug off the floor, dragging it to the vertical garden and then emerging from that jungle on hands and knees with the rug draped over her back. When she arrives in Brazil, Esther runs towards the tea cart that had previously functioned as camera and shakes the salt and pepper mills as if they were maracas and tosses the salad wildly.

With the push of a button the living room turns dark and a projection screen emerges from the floor. Dancing in the stroboscopic light of the projector, Esther turns herself into a rotoscope animation and suddenly finds herself on the front line of a battle scene. She ducks and shoots from behind the couch, then sits next to Norman and urges him to "shoot!", with his second shot killing Esther. This prompts Esther to hit Norman on the head with a pillow, resulting into a pillow fight that does honor to the term "throw pillow".

Obviously in a better mood than before Esther's supper show, Norman pulls her behind the couch with him for a small make out session far more enjoyable to them than the big finale of the production number could have ever been.

Credits:

Produced by Sidney Luft, Vern Alves (associate producer) & Jack L. Warners (executive producer); Directed by George Cukor; Screenplay by Moss Hart; Music by Harold Arlen; Lyrics by Ira Gershwin; Cinematography by Sam Leavitt; Production design by Gene Allen; Art direction by Malcolm C. Bert; Starring Judy Garland and James Mason.

Sources:

The first time 'A Star is Born' was brought to the screen was in 1937, when William A. Wellman directed Janet Gaynor and Frederic March as the stars of the picture. The 1954 remake was devised as a comeback for Judy Garland, who parted ways with MGM and filmmaking in 1950, but was riding a high after her successful concerts at the London Palladium and The Palace in New York in 1951 and 1952 respectively.

Moss Hart, author of some of the most famous plays in American theatre, was signed to write the screenplay for the remake that was to become a musical to show off Garland's talents. As no original scripts were available, Hart started off by rewatching the 1937 version various times to outline the structure, characters and situations.

For the Tour de Force number, Hart stayed true to the 1937 film, but added a musical number. As Norman (James Mason) has been let go by the studio, Esther's (Judy Garland) star is rising. In an attempt to cheer Norman up, Esther puts on a show in their living room. As written by Hart:

ESTHER:

We started shooting the big production number — and it’s the production number to end all big production numbers! It’s an American in Paris, Brazil, the Alps and the Burma Road! It’s got sex, schmaltz, patriotism, and more things coming up through the floor and down from the sky than you ever saw in your life!

She launches into the production number, taking all the parts herself – the ballet, the chorus boys, the show girls, the director, the leading man, a burlesque of herself, singing the main song, using anything she can lay her hands on in the room for props. She leaps in and off sofas, turns of chairs — it is a tour de force solely to make him forget himself and laugh. And finally he does – wholeheartedly. She falls into his arms, exhausted. Her own laughter joining happily in his.

For this scene composer Harold Arlen and lyricist Ira Gershwin wrote a song called 'Someone at Last'. It was written as a parody on musical production numbers, but incorporating all of Hart's instructions proved to be a challenge for choreographer Richard Barstow. So Garland and Sid Luft (producer of the film and Garland's husband at the time) turned to composer-arranger Roger Edens for help. Edens had worked with Garland from the beginning of her career at MGM and played an important role in shaping her voice and teaching her how to deliver a song, sometimes underplaying her voice instead of using it at full power all of the time, as she was used to doing in Vaudeville.

In early January 1954, Garland and Edens started rehearsing the number, making an audio recording of their ideas for the number. In 10 minutes and 25 seconds they play out the number, with Edens taking on the role of Esther Blodgett and Garland singing parts of the song or providing sound effects and commentary in the background. The number starts by Esther telling Norman about the big production number they started shooting, "it starts in an Orphans home, and I'm an Orphan," says Edens. The idea was that Esther would be playing an orphan who dreams of searching for the someone for her, looking for him through mist, fog and smoke, in Paris and Japan, the jungle and Brazil, eventually become a nurse for the Red Cross in the Battle of the Bulge. "You die," says Edens in a deadpan way. But then comes the big finale: the real her, still dreaming at the washtub in the orphanage, "has finally realized she's been missing an absolute bore and starts singing the finale, but they worked it out for a big, terrific shot —the finish shot, where the camera zooms in to this tremendous close-up of me, just as she starts into the finale", finally finding that someone for her.

Using this recording as a guideline, the number was reworked by Hart and orchestrated by Ray Heindorf. This fed Barstow's imagination and he started working on the choreography for the number, using the furnishings of the living room as props. The idea of the orphanage was dropped for the final number, but many of the elements that Garland and Edens had improvised stayed in the film, with the "big, fat close up" eventually becoming the figurehead of the film.

Recording of the scene began on February 4 and took four days and two cameras to finish. In the seven minutes that the number would eventually become to last, Garland dances through the living room using virtually everything she can find as a prop to illustrate the grandeur of the production number, a true tour the force to entertain Norman. A standing lamp becomes the light, a tea cart becomes the camera and jumping up on a coffee table, she's ready for action.

There's still the smoke (produced by fervently puffing on Norman's cigarette), the music of harps (a stool with its pillow removed) and voices of angels. Then in Paris Esther becomes a traffic leader, a burlesque dancer covering (and then exposing) her breasts with two leaves taken from the vertical garden on their living room wall and a can-can dancer using a ruffled pillow as skirt. In the recording Garland and Edens also improvised Edith Piaf singing "the eternal tragedy of woman", but Piaf didn't make it to the final version.

All of a sudden they are in Asia, mimicking traditional dances and donning a lampshade as a surrogate for a traditional hat. They don't stay in Asia for long, though — within a few seconds they are in Africa, with Esther grabbing the leopard skin rug off the floor, dragging it to the vertical garden and then emerging from that jungle on hands and knees with the rug draped over her back. When she arrives in Brazil, Esther runs towards the tea cart that had previously functioned as camera and shakes the salt and pepper mills as if they were maracas and tosses the salad wildly.

With the push of a button the living room turns dark and a projection screen emerges from the floor. Dancing in the stroboscopic light of the projector, Esther turns herself into a rotoscope animation and suddenly finds herself on the front line of a battle scene. She ducks and shoots from behind the couch, then sits next to Norman and urges him to "shoot!", with his second shot killing Esther. This prompts Esther to hit Norman on the head with a pillow, resulting into a pillow fight that does honor to the term "throw pillow".

Obviously in a better mood than before Esther's supper show, Norman pulls her behind the couch with him for a small make out session far more enjoyable to them than the big finale of the production number could have ever been.

Credits:

Produced by Sidney Luft, Vern Alves (associate producer) & Jack L. Warners (executive producer); Directed by George Cukor; Screenplay by Moss Hart; Music by Harold Arlen; Lyrics by Ira Gershwin; Cinematography by Sam Leavitt; Production design by Gene Allen; Art direction by Malcolm C. Bert; Starring Judy Garland and James Mason.

Sources:

- Cukor, George. A Star Is Born. Warner Brothers, 1954.

- Garland, Judy, and Roger Edens. Somewhere There’s A Someone (From “A Star Is Born”). Vol. 3. CUT! Out Takes from Hollywood’s Greatest Musicals. Out Take Records, Inc., 1977.

- Goode, Bud. “Judy’s Painting the Clouds with Sunshine.” Photoplay, November 1954.

- Hart, Moss. “A Star Is Born,” October 7, 1953. Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (Core Collection).

- Haver, Ronald. A Star Is Born: The Making of the 1954 Movie and Its 1983 Restoration. Perennial Library, 1990.

- Schechter, Scott. Judy Garland: The Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Legend. Rowman & Littlefield, 2006.

- “The Making of the 1954 Masterpiece A Star Is Born Starring Judy Garland and James Mason.” Accessed April 28, 2019. http://www.thejudyroom.com/astarisborn.html.